Gotham City Map by Eliot Brown

Gotham City layout reference maps

Read More: Smithsonian Examines Eliot R. Brown's Map Of Gotham City | https://comicsalliance.com/smithsonian-eliot-r-brown-map-gotham-city-batman/?utm_source=tsmclip&utm_medium=referral

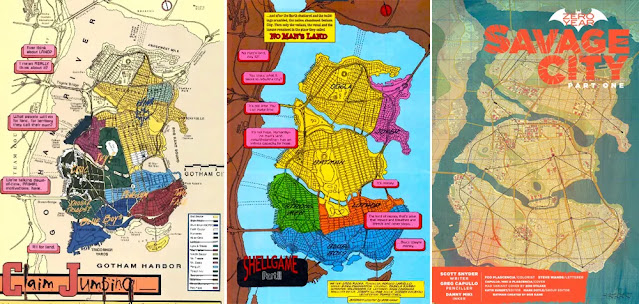

The impetus behind mapping out Gotham City was, of course, the most comic booky reasoning of all. It was created during the planning stages of No Man's Land so that the creators behind the massive earthquake that leveled Gotham could know exactly what it was they were leveling.

Before that, Gotham had existed as just a vaguely New York-ish sort of place, with loosely defined areas like the East End, Chelsea and Midtown. Brown took all of those places and laid them out on a series of islands, adding in places like Robinson Park (the massive stand-in for Central Park named for the Joker's co-creator, Jerry Robinson) that would play a big part in the story.

Of course, as Brown himself says, "defining" Gotham City isn't really defining it at all:

“If a writer wants Batman to face Croc on a glacier-bound treehouse for mutants—then that's what he writes and gets drawn. If, the next month, Batman is now chasing Harley Quinn at a 24-Hour Endurance Sports Car Race Track—poof, there it is. All right in Gotham City. Put in a better way, it is about allowing the writers to have their freedom.”

Gotham City is the perpetually dark comic book metropolis of alleys, asylums, caves, mansions, and of course, Batman. The Dark Knight of DC Comics celebrates his 75th anniversary this year but Gotham didn’t become the hometown of the Caped Crusader until 1940, when Batman co-creator Bill Finger named the city for the first time in Batman No.4. In the early days of comics, cities weren’t much more than rooftop set pieces and vaguely defined skylines, and Batman was ostensibly fighting crime in a generic city with a vague resemblance to New York, but, as Finger has said, “We didn’t call it New York because we wanted anybody in any city to identify with it.” However, since its inception Gotham has gained an identity as complex and unique as any real American metropolis and is now more closely associated with a single character than any other city in comics. Capital-M Metropolis comes close perhaps, but Superman’s city is nowhere near as interesting as Gotham, in part because Gotham has something that makes it more fully realized and more consistent in its representation than any other fictional city in comics or film: a map.

Gotham City limits were defined in 1998 in preparation for the “No Man’s Land Story” story arc, during which the city was cut off from the United States after nearly being destroyed by a cataclysmic earthquake. It was the comic book version of Escape from New York. However, before DC Comics could destroy Gotham City, there had to be a Gotham City to destroy. Enter artist and illustrator Eliot R. Brown, the cartographer of Gotham.

Brown has no formal training in cartography, but he did study architecture and had previously worked as a technical artist for Marvel Comics, where, as he told me, he was the closest thing they had to an “in-house architect and architectural renderer (and weapons designer and aerospace engineer).” He dreamt up and drew tech specs for Punisher’s weapons, Captain America’s experimental jet, and Iron Man’s armor, and the occasional superhero headquarters. But in 1998 when Brown was contacted by Denny O’Neil, a legendary comics writer and long-time Batman editor, he was faced with an even bigger request: design one of the most iconic cities in comics history. O’Neil wanted a map of Gotham as part of an in-house "bible" to help coordinate the various comics that would be affected by the earthquake. The first step for Brown was to meet with the writers and artists who shared their wish-lists for Gotham locales. As he recalls:

“The DC Comics editors made it clear that Gotham City was an idealized version of Manhattan. Like most comic book constructs, it had to do a lot of things. It needed sophistication and a seamy side. A business district and fine residences. Entertainment, meat packing, garment district, docks and their dockside business. In short all of Manhattan and Brooklyn stuffed into a … well, a nice page layout.”

With research materials in hand and a mandate that Gotham had to be an island, Brown began, like Bill Finger, with the idea of a fictionalized Manhattan. Having grown up New York, he knew it well and used his knowledge of the city to plan its fictional counterpart, sprinkling in familiar neighborhoods, parks, civic buildings, monuments, landmarks and transit infrastructure.

The city took shape in a week and, after some testy exchanges with editors and few back-and-forth faxes, Gotham’s rough coastline was finalized less than two months later. Brown’s final hand-annotated map of Gotham City included numerous bridges and tunnels ready to be dynamited by the U.S. government, as well as a few forgotten steam tunnels that might be useful to a crimefighter and his allies. Brown didn’t just design the city; he designed an implicit history that writers are still exploring.

A few issues of the "No Man’s Land" story arc opened with a map of Gotham, illustrating the shifting boundaries of a turf war that was slowly won by Batman and the Gotham City Police Department. When “No Man’s Land” ended in 1999 and Gotham returned to the status quo, rebuilt with money from Bruce Wayne and Lex Luthor and buildings designed by Gotham planner and cartographer Eliot Brown, the map of Gotham City was officially made canon.

Since "No Man’s Land," writers and artists have worked within the confines of Gotham’s borders. And some have even expanded them, including the current Batman team of writer Scott Snyder and artist Greg Capullo. A simplified version is used in video games and, most visibly, Brown’s map of Gotham was used in the recent Batman films directed by Christopher Nolan, as can be seen above in Bane’s strike map. Brown had no idea his map had been used in the new film trilogy but told me he was “delighted that they helped further the ‘reality’ of the books.”

While a map may seem like a small thing, especially for a fictional city, it really does make Gotham feel like more of a real place. So why don’t more comics map out their cities? Why isn’t there a definitive Metropolis or a definitive Star City? Besides the amount of work it takes, Brown thinks the imposition of an official map might just be too limiting for some writers and artists. “If a writer wants Batman to face Croc on a glacier-bound treehouse for mutants—then that's what he writes and gets drawn. If, the next month, Batman is now chasing Harley Quinn at a 24-Hour Endurance Sports Car Race Track—poof, there it is. All right in Gotham City. Put in a better way, it is about allowing the writers to have their freedom.”

Ideally, a city would offer unlimited possibilities. But then again, restrictions can sometimes create the best art. Current Batman writer Scott Snyder has made extensive use of Gotham’s architecture and urban design as a reflection of Batman’s (and Bruce Wayne’s) consciousness and, in so doing, has told fascinating, layered stories rich with metaphor, history, and symbolism, including a mini-series, The Gates of Gotham, about the engineers who designed and built the many bridges that Eliot Brown created for Gotham. Brown no longer works in comics but since he created his map, writers and artists have continued to tell their stories within the confines of Gotham’s borders, and in so doing, have added to the city’s history, creating and exploring the nooks, crannies, alleys, and fire escapes of unique neighborhoods that were once nothing more than a name on paper.

Sources:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/cartographer-gotham-city-180951594/?no-ist

https://comicsalliance.com/smithsonian-eliot-r-brown-map-gotham-city-batman/

Comments

Post a Comment